‘He’s Not Charismatic. … I Think That Has Been Part of His Success’

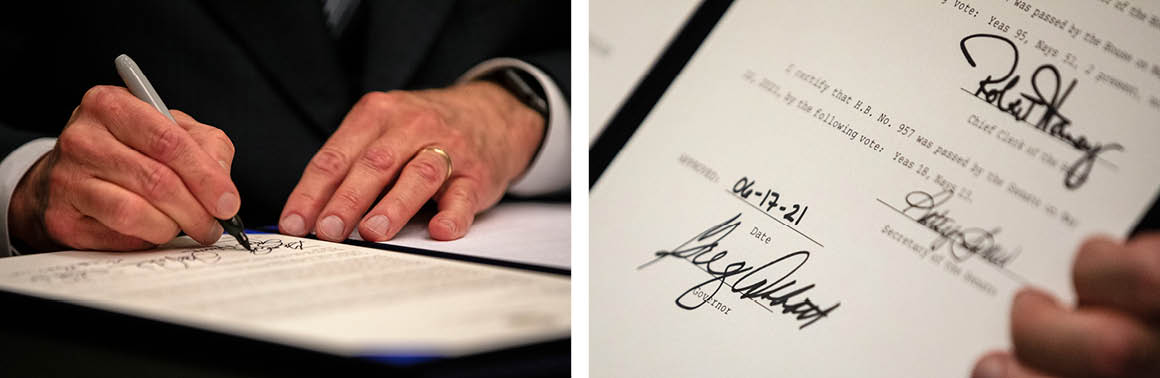

AUSTIN, Texas — On a muggy morning in mid-June, Gov. Greg Abbott wheeled into a crowded event hall on the grounds of the Alamo in San Antonio to celebrate the signing of one of the most gun-friendly laws ever passed in Texas. Once the law took effect, most Texans over the age of 21 — the adult population of the nation’s second-largest state — would be able to carry handguns, concealed or openly, with no license and without taking a safety course.

Abbott was surrounded by Lieutenant Gov. Dan Patrick, Texas House Speaker Dade Phelan and the head of the National Rifle Association, Wayne LaPierre. An unmasked audience, including grassroots activists and lawmakers’ families, filled the low-ceilinged, windowless room with the energy of a political rally. They booed when a Univision reporter asked a question about a recent shooting in Austin. They cheered when Abbott, his face breaking into a wide grin, mused that the San Antonio-based reporter must be from out of state. Someone in the crowd chanted, “Build a wall!” as the governor spoke, and a young boy screamed, “Go, Abbott!”

In one sense, it was strange the event was happening at all. The gun law hadn’t been Abbott’s idea — in fact, for months, he had avoided saying whether he supported it. The policy had spent years languishing in Texas, failing to get much traction even in a Republican-dominated legislature; Texas voters and law enforcement officials wouldn’t get behind the policy. Then, this past spring, a group of conservative activists succeeded in getting the bill passed in the Texas House. When it looked inevitable in the Senate as well, the governor finally threw his support behind the bill, signed it and organized the Alamo ceremony to mark the occasion.

For many political watchers in and outside Texas, Greg Abbott is a political puzzle. He’s not a conservative firebrand. He lacks the star power of his predecessors — the folksiness of Rick Perry; the swagger of George W. Bush; the famously sharp wit of Ann Richards. Alamo ceremony aside, Abbott generally shies away from raucous rallies in favor of local television appearances, which he does from a studio he had custom-built in his Austin campaign office. He didn’t attend the Conservative Political Action Conference in Dallas in July, which featured President Donald Trump. Abbott’s awkwardness in front of crowds emerged in flashes at the Alamo: The audience listened patiently as he made a clumsy connection between the fort’s 19th-century defenders and modern-day gun rights. “They knew the reason why somebody needed to carry a weapon was far more than just to use it to kill games that they would eat,” he said, his voice turning somewhat robotic as he spoke into a microphone. When he paused, waiting for applause to die down, Abbott’s brown eyes narrowed on his notes, and the deep grooves settled in his face.

Yet, in a state with no lack of lively, crowd-winning politicians, Abbott, 63, is dominating the field for an election that doesn’t happen until November 2022. Without the national profile of his other red-state counterparts like Florida’s Ron DeSantis, without a distinct policy platform and with near-constant pressure from Texas’ conservative base to shift further right, Abbott — who has never lost an election — seems like a shoo-in for a third term. He has raised $55 million, the largest sum ever for a statewide candidate in Texas, and he has earned Trump’s endorsement — all before officially announcing he’s running. At the moment, no competitive Democratic challenger has emerged, though the sheer amount of chatter parsing actor Matthew McConaughey’s mixed signals about a gubernatorial run indicate there’s an appetite for someone, anyone, to stir things up.

What explains Abbott’s grip on power in the country’s biggest red state? In conversations with dozens of current and former aides, lawmakers, political operatives, lobbyists and pundits over recent months, the answer that emerged was less about the sober-mannered version of Abbott that most Texans know from his TV appearances during hurricanes, winter storms or the pandemic, which has emerged yet again as a political flash point. Instead, it was about the version of Abbott these sources see behind the scenes: a former Texas Supreme Court justice and attorney general who has learned to adapt to Texas’ changing Republican electorate and anticipate potential political threats. In a state that has a history of larger-than-life political characters, the two-term Texas governor is a ruthless backstage operator, taking no uncalculated risks, figuring out how to keep donors happy and lawmakers in line, deflecting blame for crises, maintaining a massive field operation and maneuvering among the state’s disparate GOP factions.

“He’s not charismatic to the same heights as Perry and Bush were,” Republican pollster Derek Ryan says of Abbott. “I think that has been part of his success. He’s been able to keep his head down and focus on the work in front of him and let that do the speaking for him.”

Both detractors and admirers use the word “judicial” to describe Abbott. To his detractors, Abbott is reactive and overly cautious; to admirers, he’s thoughtful and deliberate. He is known to clock in long hours surrounded by a tight and loyal staff who help him plot every move, from his wardrobe — “disaster casual” is what’s on his schedule after storms — to minute-by-minute scheduling of events and even downtime. “Greg Abbott doesn’t do anything without thinking it through,” says John Wittman, who was the governor’s communications director until March.

Over the course of his seven years in office, Abbott hasn’t made any indelible gaffes — he would never forget the name of a Cabinet agency he wanted to abolish, as Perry did in a presidential debate — but he hasn’t left a distinct legacy either. Abbott’s most memorable line — about getting up every day to sue the Obama administration — is almost a decade old now, from his days as Texas attorney general. At a time when Trump has forced national Republicans to prove their loyalty, Abbott has managed to avoid being pigeonholed within the party. His dominance of Texas politics comes not so much from any vision he has laid out — he’s largely abandoned some his early, more moderate priorities like expanding pre-K — but from a shrewd political strategy that has helped him weave together a coalition of Trump fans, never-Trumpers and centrists in Texas.

Abbott’s political dance around the gun legislation represents a familiar strategy of his when it comes to controversial policies: avoiding specifics for as long as possible and getting on board only once the outcome is clear. More recently, as Covid cases have surged in the state and overwhelmed the healthcare system, Abbott has enlisted medical personnel from out of state and requested that hospitals postpone elective procedures — while banning mask and vaccine mandates. These moves appear to be aimed directly at Republican voters: In the 2022 gubernatorial election, Abbott faces at least three GOP primary challengers who have spent much of the past year questioning his conservative credentials, most pointedly over the governor’s Covid restrictions last year. In an effort to box out the competition, Abbott, in turn, has spent the summer taking up divisive causes like building a wall on the Southern border, arresting border crossers, limiting transgender rights and urging the state legislature to pass voting restrictions and empower partisan poll watchers.

While his balancing act has worked so far, the 2022 Republican primary could still turn out to be Abbott’s most competitive yet — if any of his challengers gain traction, he could be forced into a runoff. Some moderate Republicans, meanwhile, worry the powerful governor already has swung too far to the right in recent months to appease a small group of vocal voters. Other observers say Abbott’s low-key demeanor could be a liability if he considers a run for national office in 2024 — as many have speculated. Abbott was at 1 percent in a July CPAC presidential straw poll.

The governor is “kind of a recluse,” says Texas Agriculture Commissioner, Sid Miller, who considered challenging Abbott in the governor’s race but decided to run for reelection himself. “It’s kind of like dealing with Sasquatch,” Miller, a Trump ally who protested Abbott’s pandemic restrictions last year, told me in his taxidermy-filled office. “They know he’s out there, but no one ever sees it.”

When I met Abbott back at his office in Austin a few hours after the San Antonio visit — a far more understated space than Miller’s — I asked the governor whether he thought President Joe Biden had won the November election. Abbott had been threatening to call a special session of the state legislature to pass election reform measures — a promise he made good on days after our conversation. But instead of answering the most existential question for any Republican politician in this moment, he launched into a lengthy explanation of how getting rid of voter fraud was a bipartisan issue. I pointed out that Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton had sued to overturn election results in other states. While Abbott didn’t exactly embrace the move, he didn’t criticize it either. As in much of our conversation, he avoided saying anything that would upset any one faction of the Republican Party, which meant sidestepping specifics. And, in this case, he made it clear that he wasn’t going to tell me what he really thinks.

“I will abide by what the courts have decided,” Abbott finally said.

Few people doubt Greg Abbott’s Republican bona fides, but many who have known him for years say he is personally more moderate than his public persona these days. When we spoke in June, he talked about focusing on “bread-and-butter fundamental issues” and creating “an environment where any Texan has the ability to get a job” — a far cry from the issues he has promoted this summer. In his 2016 memoir, Broken But Unbowed, Abbott writes about lawsuits he filed against the Obama administration as attorney general, his first campaign for governor and his views about the constitution and Congress. But the memoir also includes details about his own biography and his vision for a multicultural Republican Party. Abbott’s wife, Cecilia, whom he met when they shared a dorm at the University of Texas, is the granddaughter of Mexican immigrants.

In 1984, when Abbott was 26, he and a friend took a break from studying for the Texas bar exam to go for a jog in Houston. About 10 minutes into the run, an oak tree fell on Abbott, paralyzing him permanently from the waist down. His memoir openly discusses the daily challenges that followed as he navigated life in a wheelchair: falling out onto a curb on his way to taking the bar exam, learning to drive with hand controls, having to argue a case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court from the counsel table instead of the customary podium. It complicates his ability to campaign and travel. Former staffers say the accident — and his ability to recover — have given Abbott an intense focus on his job and a moral compass. Some argue it softens his image as a politician.

Abbott has always confronted Democrats aggressively, but he has a history of advocating for policies that all Republicans can get on board with, like cracking down on human trafficking. When he ran for governor the first time, in 2014, he appealed to traditional conservative causes such as education, ethics reform, low taxes and border spending. The next year, in his first state of the state address, he identified university research and transportation among other “emergency” issues for the state.

But Abbott’s ascent in Texas has coincided with the Republican Party’s move toward Tea Party populism, then Trumpism, and unlike Perry and Bush, Abbott also has only led Texas when it’s been a one-party state. (Both former governors declined to comment about Abbott.) The same year that Abbott became governor, Dan Patrick, a former talk radio host and state senator, knocked off three-term incumbent and moderate David Dewhurst in the Republican primary for lieutenant governor. It revealed to old-guard Texas Republicans two years before Trump was elected president the extent to which grassroots, socially conservative agitators could outflank the traditional business-friendly wing of the GOP.

The agitators’ pull on Abbott became apparent early on in his tenure. During his first year in office, conspiracy theorists stoked fears that Jade Helm 15, a routine U.S. military training exercise taking place in in Texas and other states, would be a precursor to martial law. After conservative media outlets latched onto the theory, Abbott requested that the Texas State Guard monitor the operation, saying the move was meant to “provide information for people who have questions.” For Matthew Dowd, chief strategist for Bush’s 2004 presidential election, it was the first sign that Abbott would cave to far-right pressure even if it meant lending credibility to fringe groups. “For him to do that when it was a complete fiction,” Dowd says, “that was my first indication that Abbott has given up all sense of leading as a principled conservative.” (Abbott’s spokesperson, Mark Miner, said in an email that the governor was responding to local concerns about “the lack of transparency surrounding large military training operations taking place in their vicinity.”)

Abbott, though, has been strategic about when he moves to the right, and just how far to go. The Texas electorate overall has nudged to the left in recent years, and business interests still hold sway here. Take the 2017 debate over the state’s “bathroom bill.” In Texas, lawmakers meet for a regular session that lasts 140 days every other year; only the governor can call a special session. That year, under pressure from Patrick and grassroots activists, Abbott included in his call for a special session a bill proposing to restrict bathroom use for transgender people. The business community furiously lobbied against the proposed legislation, saying it would destroy companies’ ability to recruit and retain staff in Texas.

Caught between two factions of his own party, Abbott worked behind the scenes to make sure the bill he had publicly supported wouldn’t actually get to his desk. His staffers descended on the office of state Rep. Byron Cook, who chaired the House State Affairs Committee and had the power to keep the bill from making it to the floor, and pressured Cook not to let the bill through, Cook recalled in an interview. Cook and other moderate Republicans ultimately kept the bill from getting a floor vote. Publicly, Abbott blamed Cook and other House lawmakers for not passing the bill.

“He played both sides,” Cook says. Cook, who did not seek reelection in 2018, argues the bill’s failure made it easier for large tech companies to move into Texas in recent years. “Incredibly, the same state leaders that pushed for the bathroom bill — they ballyhoo and take credit every time one of these technology companies come to Texas,” he says. “But I promise it wouldn’t have happened if the bathroom bill would have passed.” Abbott’s spokesperson called Cook’s allegations “false” but did not elaborate. Another former Republican lawmaker and a lobbyist involved with the bill confirmed Cook’s version of events.

When I asked Abbott in June where he fits on the ideological spectrum of the modern Republican Party, he avoided pinning himself down. He talked in broad strokes about the issues all Republican politicians talk about, like jobs and safety. “This is a place I’ve been ever since I’ve been in office, and that is a strong conservative,” Abbott said. “I was that way as a judge. I was that way as an attorney general. And I’ve been that way during my entire tenure as governor.”

There is a constant rumor in Texas that Patrick, who suggested last summer that grandparents would be willing to die of Covid to save the economy, will primary Abbott. Some point out that he still could. But it hasn’t happened yet. Nor have others succeeded. In 2014 and 2018, Abbott won his Republican primaries with more than 90 percent of the vote. He also won both his general election challenges by double-digit margins, going after his Democratic opponents for being too far to the left and deploying an expensive operation to target and turn out voters.

“Abbott persevered through several rounds of that,” says James Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas. “People underestimate his political strength and his adaptability — and ‘adaptability’ is a polite term. … He has been politically pretty fluid through the length of his governorship.”

With a 2022 election more than a year away, Abbott is now in the midst of another round of navigating between primary and general election voters. His apparent worry over his long-shot Republican primary challengers can be traced back to last fall.

In a late September special election for an open state Senate seat, Shelley Luther, who spent several days in jail last year for reopening her Salon à la Mode during a statewide Covid shutdown order, won 115 more votes than Drew Springer, a state representative who had largely run unopposed after winning his first election in 2012. The two Republican candidates were forced into a December runoff for the district, which stretches northwest of Dallas.

Luther, who raised more than a $1 million, made the election a referendum on Abbott’s conservative credentials, arguing that the governor’s pandemic restrictions amounted to tyranny and that Springer was part of the Austin swamp that had enabled Abbott. Abbott and his team rallied for Springer in the runoff: The governor filmed an endorsement video, his campaign gave more than a quarter-million dollars in in-kind donations, and it aired an attack ad against Luther.

In the end, Springer beat Luther by 13 percentage points, but the message was clear: A faction of the GOP in Texas was out to get Abbott, and if he was going to win his own primary decisively, he would once again have to maneuver to the right to win over detractors. That’s meant that this summer, even as Covid patients fill Texas hospitals and as teachers worry about school outbreaks, Abbott has refused to let local governments and school districts implement mask mandates and other virus mitigation measures. Some local leaders are openly defying the governor’s orders by issuing mask mandates nonetheless and challenging the mandate bans in court.

Abbott is now facing at least three challengers in next year’s GOP primary: Don Huffines, a former state senator, whose billboards lining Texas highways call for an end to property taxes; Allen West, a former Florida Tea Party congressman who moved to Texas and became state Republican Party chair; and Chad Prather, a conservative commentator and comedian. West has accused Abbott of not doing enough to advance conservative priorities on the border and on gender-affirming care for transgender children. He also argues Abbott has been too soft on state House Democrats who left Texas for Washington this summer to deny the legislature the quorum needed to pass voting restrictions — West said that as governor he would have called special elections to replace those Democrats. “Who do you want in the arena?” West told a radio interviewer. “Do you want someone who will go into the arena and fight for you? Or do you want someone who will take the weaker path?”

Abbott’s approval rating is nearly 80 percent among Republican voters, according to the Texas Politics Project. Most of the grassroots activists I spoke to at the June bill signing in San Antonio said they supported Abbott, especially after his responsiveness this year to the issues they care about. But Stephen Willeford, who was feted at the event for disrupting the deadliest mass shooting in Texas history with his AR-15, was still holding out judgment. Willeford became famous in 2017 for confronting the gunman who killed more than two dozen people at a Sutherland Springs church. He now has a YouTube channel called BareFoot Defender — he wasn’t wearing shoes when he stopped the attack — where he has invited all the gubernatorial candidates to appear. So far, West and Huffines have agreed.

“Allen West is very conservative, and he talks my game. So does Huffines, and so does Prather,” Willeford told me when I caught up with him over the phone in late July, to see if he had made up his mind about the primary. He hasn’t. “For the most part, Abbott does too,” he added.

This summer, Abbott is leaving nothing to chance in his effort to fend off the challengers and win over the undecideds. He raised $18.7 million just in the last 10 days of June. Four donors have given $1 million each, including Dallas billionaire Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, a gas pipeline company that made $2.4 billion this past winter when the state was in the grip of a major winter storm that left millions without power for days. Abbott’s relentless fundraising, which fuels an expansive voter outreach effort, is another key reason he has held onto power. The governor devotes an enormous amount of time to the task, those who know him say, making donor calls himself armed with extensive notes. For five business days in late June, Abbott’s schedule had been blocked off in advance for fundraising calls.

Bill Miller, founder of the lobbying firm HillCo Partners, which donated $55,000 to Abbott’s reelection bid this year, says he knows that when Abbott calls, the governor will ask about his daughter, who, like Abbott’s daughter, Audrey, attended the University of Southern California. Miller knows Abbott will have time to chat about issues or listen to requests for favors. And while Abbott might come off as stiff in public appearances, in one-on-one calls and meetings, donors say he is warm, friendly and even charming. “He takes the time to work the deal,” says Miller. “That’s what separates the good from the great. And he’s great.”

Some sources say that Abbott is less accessible to those who aren’t key to his political success, however. Clay Jenkins, a Democrat who since 2011 has been the highest elected official in Dallas County, says he talked to Rick Perry once or twice a day when Dallas had an Ebola scare. But Jenkins, who asked a judge on Monday to block the governor’s mask mandate ban, says he talked to Abbott maybe once during the entire pandemic. Jenkins says he didn’t talk to the governor at all in February during the deadly winter storm. “I don’t have his email or cell,” Jenkins says. (Abbott’s spokesperson said the governor is in close communications with other local officials who have “no issue picking up the phone and calling the governor or his staff.”)

In addition to fundraising, Abbott has spent the past couple of months ramping up his effort to court Republican primary voters. On June 1, the day after the regular Texas legislative session ended, he made two calls to Trump, according to a copy of the governor’s schedule; the former president endorsed Abbott that same day. Later in the month, Abbott and Trump held a joint appearance in South Texas about border security. The governor just called a second special session — after Democrats brought the first one to a halt by leaving the state — to take up the voting reform bill, as well as a bill that would dictate which sports teams transgender kids could play on and another bill banning critical race theory in schools, even though similar legislation passed during the regular session. Last Friday, Abbott directed a state agency to determine whether some gender confirmation surgeries counted as child abuse.

Some Texas Republican strategists, lawmakers and others familiar with Abbott’s operations worry he already has moved too far to the right. After all, he’s the front runner, with loads of money in the bank. They say he should use his perch at top of the state to set the agenda and not react to it. Plus, Abbott will never be able to satisfy the hardline conservative activists who oppose him and actively support his primary challengers.

“We are dealing with issues that are being brought up by Gov. DeSantis in Florida, and we are just trying to keep up with the Joneses,” says Lyle Larson, a moderate Republican state representative who has previously clashed with Abbott. Larson argues the special sessions could have been opportunities to shore up the state’s power grid or address issues like healthcare and education, rather than injecting Texas into the national culture wars. “I think a lot of legislators are scratching their head trying to figure out why we are coming back.”

Even though Abbott has an air of inevitability, August is too early to say that the race is a throwaway. The deadline for primary candidates to file isn’t until December, and it’s likely to get extended because redistricting has yet to take place following the delayed release of U.S. Census data. There are a lot of dark-horse threats lurking for Abbott in the next year and a half. Covid cases continue to soar in the state. The Texas power grid could fail again with peak summer heat or another winter freeze. There could be another mass shooting. The economy could tank. Matthew McConaughey could actually decide to run.

At the moment, though, Democrats aren’t posing much of a threat. Some party insiders are pinning their hopes on Beto O’Rourke, arguing he is the only Democrat who could match Abbott’s fundraising abilities; in the 2018 U.S. Senate race, Abbott’s campaign handled voter mobilization efforts for Senator Ted Cruz, propelling his victory over O’Rourke. O’Rourke says that for now he’s focused on voting rights and hasn’t decided on another statewide run. Other Democrats sense an opening for a more moderate candidate to challenge Abbott in the general election.

Still, Democrats face the heaviest of headwinds in 2022. It’s a midterm election year with a Democrat in the White House. Abbott is a term-two incumbent with lots of money and wide name recognition. And even though Texas is becoming more urban and suburban, Democrats have struggled to win over Abbott voters. Wendy Davis and Lupe Valdez, who ran against him in 2014 and 2018, respectively, each earned only about 40 percent of the vote.

“There is no way to sugar-coat it,” says Ed Espinoza, executive director of Progress Texas, a progressive media group. “2022 is going to be a tough year.”

Abbott’s political legacy has been formidable. Candidates have to raise eye-popping amounts just to keep up, and his campaign cash has fueled Republican victories across the state. Even February’s winter storm, which led to about $130 billion in lost output and damage according to one estimate, has barely dented Abbott’s approval ratings. That’s another crisis that Abbott survived, by pointing the finger at the state’s grid operator, even though his office failed to deliver warnings about the potential outages and his appointees failed to prevent the disaster.

His policy legacy is far less clear. It’s hard to know where Abbott will leave the Texas Republican Party and the state in five years if he does win again. It’s hard to know how he would stand out from other high-profile candidates if he pursues national office. Dave Carney, Abbott’s political adviser, says the governor will lay out his 2030 vision for the state in due time during the campaign. But, so far, his actions this summer have sent a mixed message.

When I asked the governor directly about his vision for the state, he said: “Any other candidate who tries to run would be basically adopting the vision that I’ve already cast and the vision that I have cemented for Texas, which is the conservative vision where Texas is a conservative paradigm for the entire country.”

Abbott has a way of making even the most divisive, hot-button issues seem dull, signaling support for certain priorities while neutering their impact — and that, too, is surely part of his success.

The day before the bill signing in San Antonio, he held another press conference in the governor’s reception room at the capitol in Austin to announce that the state would pick up Trump’s signature proposal of building a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border with donated land and funds. He maneuvered his wheelchair across a peacock green carpet and positioned himself at a low table covered with a black tablecloth. Behind him, three rows of Texas lawmakers squeezed together on raised daises.

Abbott spoke about how people crossing the border were invading Texas and described a scene of chaos at South Texas ranches. The choice of words upset many Democrats. They argued that it echoed language from a gunman who killed 23 people at an El Paso Walmart two years ago. (Abbott told me he wasn’t worried about the parallel, but about the people who live on the border.) Then, after the fiery speech, Abbott announced his first concrete step toward building a wall, something that made me feel more like I was at a Wednesday office meeting than a fired-up Trump rally: a letter directing a state agency to hire a project manager to oversee the process.

At first, the room reacted with silence as Abbott methodically explained the step. Hesitant applause broke out as he reached for a pen and started to sign the declaration. “Building the wall in Texas,” Abbott said, holding up the letter to the cameras, “has officially begun.” Abbott appeared to be searching for a dramatic moment. But a second later he looked down at his notes again and moved to the next order of business.